5 NON-FICTION BOOKS OF ALL TIME

The best non-fiction books can educate readers on

vital subjects, offer fresh new perspectives, or simply give us a valuable, and

often entertaining, insight into the lives of others. Here is our edit of the

must-read new non-fiction, and the best non-fiction books of all time.

CODE DEPENDENT

LIVING IN THE SHADOW OF

AI

A fascinating, sobering, wide-ranging examination.

SHORTLISTED FOR THE WOMEN'S

PRIZE FOR NON-FICTION 2024

Murgia,

a British-Indian tech writer for the Financial Times, has spent ten years

researching artificial intelligence (AI) (formerly for wired magazine). Her

travels have taken readers to Salta, Argentina, Nairobi, Amsterdam, and the

remote Indian village of Chinchpada. The author defines AI as "a complex

statistical software applied to finding patterns in large sets of real-world

data," of which ChatGPT and other generative AI tools are a

"subset." The author then examines the effects of AI on those who

use, train, and is harmed by it. Low-wage workers who classify and describe

photos that could be used to train self-driving cars, for example, fall into

the first category; healthcare providers in impoverished areas who utilize

AI-powered apps to help with diagnosis fall into the second. The victims of AI

are numerous: Uyghurs living in China's surveillance state; women whose

deepfaked images are widely circulated on pornographic websites; Uber Eats

drivers whose wages are reduced by the algorithm; and content moderators

compelled to spend hours on end interacting with violent, hateful content. With

chapter headings like "Your Livelihood, Your Body, Your Freedom, Your

Safety Net," which highlight how AI affects the person, the survey is

filled with beautifully rendered issues that aid readers in understanding AI

and its impact on a deeply personal level.

In

addition to focusing on the "global precariat," Murgia has

purposefully extended her reach beyond Silicon Valley. This approach is

valuable in and of itself, as it highlights the extent to which the developed

world is deeply connected to the ongoing evils experienced by the poor world.

The author writes with compassion and clarity in equal measure throughout.

Dead Weight

Essays on Hunger and Harm

by Emmeline Clein

Book Summary

An intimate and societal examination of the deadly culture of

compulsive eating that has resulted from the dark side of Western beauty

standards

In Dead Weight, Emmeline Clein shares the accounts of other

women—historical personalities, pop culture icons, and the females she's known

and loved—along with her own battle with disordered eating. By telling the tale

of her own illness, presenting the unvarnished memories of interview subjects,

and sending readers down social media rabbit holes, Clein breaks stereotypes

and makes statistics and science feel urgently personal. From her early

experiences with representations of the idealized slim to her years of

oscillating between starvation and overindulgence, from the pro-anorexia blog

that unintentionally saved a life to the residential treatment facilities that

exacerbate the illnesses of many others, from a wrenching elegy for those who

didn't survive to a manifesto for sisterhood, solidarity, and recovery, Clein

uncovers girlhood's appetites and injuries to reveal the economic, cultural,

and political history of an epidemic.

According to Dead Weight, there is a pernicious American religion

of femininity that is based on racism and misogyny, and it is a culture of

self-denial, self-harm, and suppression. Clein explores the economic factors

that underlie diet culture and the ways that modern feminism may contribute to the

fetish of self-shrinking by tracing the medical and cultural histories of

anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating disorder as well as the recent emergence of

orthorexia.

Drawing from a wide range of sources, including the writings of

Simone Weil, Chris Kraus, and Anne Boyer, the medieval canon of anorexic

saints, and cult classic movies like Jennifer's Body, the aughts-era

Tumblrverse, and more, Clein advocates for a feminism that doesn't force women

to reduce their bodies in order to increase their value, urging radical

acceptance of all our appetites instead: for food, connection, and love. A

sharp, perceptive, and revelatory polemic about the external forces that shape

our lives, Dead Weight is electrifying, unapologetically bold, and fiercely

compassionate.

HERESY; Jesus Christ and

other sons of God

Catherine Nixey

From Herod as the Messiah to a virginity test for

Mary – the Christian story, but not as you know it.

When it comes to nativity tale variations, the one found in James'

Gospel from the second century is quite good. It begins fairly elegantly,

describing how the earth abruptly stops rotating at the moment of Jesus's

birth: birds dangle in the air, a shepherd's arm is paralyzed, and the stars

remain motionless. Shortly after, a woman shows up, doubting Mary's ability to

be a virgin. She pushes her finger up the new mother's vagina, causing her hand

to burn off instantly. "Woe," the woman exclaims. Perhaps because she

believed she had made her point, Mary's response is not documented.

This is only one of

the many different forms of Christianity that flourished in the years that

followed the life and death of Jesus—hundreds, if not thousands. Consider the

Ophites, who thought Christ had come to Earth in the guise of a serpent. Their

method of celebrating mass involved consecrating the loaves by coaxing a snake

to slither over the altar. Another group from the first century AD thought that

their long-awaited Messiah was King Herod, not Jesus. Pontius Pilate, on the

other hand, was viewed in Ethiopia as much more than just a ponderous Roman

middle manager. Even now, he is still regarded as a saint there.

And that's not even

getting to the Apocrypha, those antiquated writings that provide a sort of

gospel-through-a-looking-glass interpretation and teeter on the verge of

validity. You will read here about Mary's ability to breathe fire and how the

young Jesus was revered by dragons. Usually, the tone is really agitated.

Another account describes how Herod's mother unintentionally severed her

daughter's head while worms sprung out of her father's lips. The icing on the

cake is a hint of necrophilia and talking donkeys.

According to

Catherine Nixey in this captivating book, the early Church Fathers moved heaven

and everything to ensure that these egregious versions of the Christian story

were nipped in the bud. They labeled anything they came upon as

"heresy" and threw the book at it, whether it was a text, a behavior,

or a belief that they hadn't approved. The obvious punishments were flogging,

fines, and exile. However, the most effective way to send a message was to row

heretics out to sea, toss them overboard, and weigh them down with a sack of sand

attached to their neck and legs. Ensuring that nobody could be found and used

as a source of devotion was the goal. Only one form of Christianity endured and

prospered as a result of such oppressive policies. That is the Christianity

found in the King James Bible, Bach's Magnificat, Milton's Paradise Lost, and

the Sistine Chapel.

"Heresy would

tilt European history for centuries," according to Nixey. Galileo would be

placed under house arrest and Martin Luther would be excommunicated as a

result. Thomas Cranmer was inspired to write the Book of Common Prayer in 1549

by heresy, or rather, by his fear of it. British bishops tried to pass a vote

of censure in 1947 over the heresy of a fellow bishop who had written a book

rejecting the virgin birth. Even if they were unsuccessful, the fact that they

felt it was worthwhile to attempt speaks something about heresy's enduring

power to unnerve and even shock people. Nixey tells us at the outset of this

enlightening tale that she was raised by a former nun and monk and considered

herself a devout Roman Catholic up until the late 20s. Then, there is nothing

gloomy about her amazing writing, yet you will notice sporadic bursts of rage

as she describes some horrible instance of repression and censorship.

What comes through is

a sort of irritated affection for the customs that she was raised in, as well

as an uncontrollably funny giggle at the notion of a Virgin Mary who shoots

flames out of every opening as though it were a Marvel superpower.

Space Oddities: The Mysterious

Anomalies Challenging Our Understanding of the Universe

HARRY

CLIFF

A prominent

experimental physicist and science presenter looks at how new data is

challenging established scientific theories, concepts, and paradigms.

Cliff states,

"Science does not progress in a straight line, running from ignorance to

understanding." Cliff works as a particle physicist at the Large Hadron

Collider at CERN and Cambridge University. "It's a messy business, with

lots of wrong turns, false starts, and dead ends." The author certainly

possesses the qualifications to explain why physicists are facing a plethora of

new mysteries at the moment. A sense of comfort has grown over several decades,

but in recent years, a number of anomalies have challenged the long-held

beliefs. For instance, why are stars vanishing more quickly than predicted? Why

do neutrinos not behave in the ways predicted by theory?

What are the intense

energy bursts that periodically break through the Antarctic ice? Cliff talks

about his travels throughout the globe, his visits to research centers, and his

interviews with some of the people who are looking for solutions. Theorists who

rely on intricate mathematical models and observers who emphasize links and

experiments are at odds with one another. There is a sense of searching for

fresh perspectives and original ways to define reality on both sides. One issue

with the book is that, even though Cliff tries to describe the concepts in

terms that are understandable to non-specialists, particle physics and

cosmology are very complex fields, and some of the writing is hard to

comprehend.

The content is

challenging for general readers, but it will be fascinating for anyone with a

foundation in advanced physics. Cliff, however, comes out as optimistic,

humorous, and passionate about his subject: "Nature does not readily

reveal her secrets; one must fight for them. However, this meandering path

ultimately does inevitably lead to a greater comprehension.

A reliable analysis

of recently discovered scientific issues.

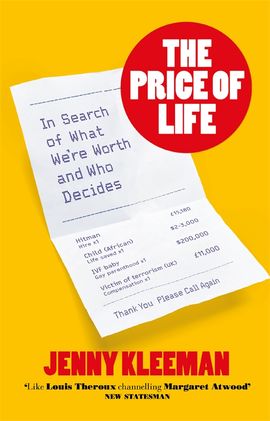

The Price of Life by Jenny Kleeman review – what’s it worth?

A riveting

examination of the value we place on human life – from healthcare to hitmen

Governor Andrew Cuomo

of New York faced pressure to ease Covid limits at the beginning of May 2020.

In a televised speech, he stated, "The quicker we reopen, the lower the

economic cost, but the higher the human cost because the more lives lost."

The topic of the value of a human life resurfaces. Nobody is openly or freely

admitting the genuine conversation, but we should.

The focus of this

captivating work is that forbidden question. Although we may be reluctant to

talk about it, the cost of a human life is always being determined behind

closed doors. So who is making these decisions, why are they being made, and by

what standards? And what do the numbers show about who – or what – we value?

Journalist and

broadcaster Jenny Kleeman met scientists and entrepreneurs at the forefront of

technological innovation for her first book, Sex Robots & Vegan Meat. Once

more, she interviews people who control the algorithmic scales and others whose

lives are at risk in an effort to find human stories that translate the

impersonal into something understandable.

The price on someone's

head is where we start. A former hitman and Kleeman have supper together.

Although he is hesitant to discuss figures, she finds out that the typical

bounty in the UK is roughly £15,000. She learns about the horrific experiences

of Vietnamese women who were brought into Britain as domestic slaves. She pays

a visit to the family of retired Tunbridge Wells couple Rachel and Paul

Chandler, who were abducted by Somali pirates while sailing in 2009. The

British government won’t pay ransoms, so the couple’s family had to negotiate

it themselves. The average global demand in 2021 was $368,901.

Kleeman takes a tour

of the Lockheed Martin facility in Fort Worth, Texas, which produces the

world's priciest weaponry, the F-35 fighter plane. Kleeman divides the cost of

a plane, which is roughly $110 million, by the approximate number of lives it

has claimed in order to calculate the cost of those lives. She acknowledges

that the answer is, to put it mildly, ambiguous, but it still begs the question

of why there is a killing machine this expensive.

Although payouts from

life insurance only depend on premiums paid, you would expect it to offer a

more accurate gauge. Actuaries evaluate your propensity for longevity, not your

net worth. The families of murder victims will get £11,000 from the Criminal

Injuries Compensation Authority. More is compensated for a severe injury that

includes lifelong care.

The families of those

who were stabbed to death in the 2017 terrorist assault on the London Bridge

were entitled to statutory compensation, but the victims of the van the

perpetrators were driving were given millions of dollars by the rental business

Hertz. Payouts from commercial insurance differ greatly from one another; they

are meant to cover the financial and psychological burden on surviving family

members rather than the loss of a life.

Kleeman demonstrates

how social standing, place of residence, market dynamics, and random chance all

affect prices. While certain variances highlight injustice, others have less

significance and are more difficult to compare. The £200 to hire a killer or

the $500 to purchase an Afghani child bride are, as Kleeman admits, actually

indicators of desperation. When we get at the more abstract top-down allocation

of resources, the necessary weighing of one life against another, that this

book provides the most satisfying answers to the philosophical questions posed

with such thoughtful clarity at the start.

Effective altruism

proponents think that rather putting a leaflet via the letterbox with a picture

of an injured dog, charitable donations should be decided by a cool-headed

estimate of the benefits. When it comes to altruism, those who are effective

will put helping a stranger on the other side of the globe ahead of assisting a

homeless person on your street if doing so will provide greater results. If the

life is in Africa, they will teach you how to save it for as little as $4,500,

since those are the least expensive. One supporter obsesses with the ideal age

to preserve a person's life. "I believe the passing of an eight-year-old

represents my peak value," he states

The National

Institute for Health and Care Excellence (Nice) in England and Wales must be

equally objective, but in the service of a cash-strapped NHS rather than

billionaires’ consciences. Its fascinating, largely private deliberations use a

metric known as a Qaly, or quality-adjusted life year, which is worth

£20,000–30,000 and represents one year of good health. If a drug costs that

much or less for each additional year of good health it provides for a patient,

Nice will approve it.

Kleeman meets the

mother of a child who was barely old enough to receive the priciest medication

in the world due to a unique hereditary illness. Through the media, she made an

appeal to Nice, and it gave in and revealed its human side. The organization

must balance the conflicting interests of the individual and the group; in the

words of the mother, "I understand that money isn't an endless source, but

when it's your child...." Market capitalism greatly exacerbates this

dilemma. "There will be a price on life as long as pharmaceutical

companies are run for profit," says Kleeman.

Her work, which makes

one think of Shylock's pound of flesh and his muffling of ducats and daughters,

is a mind-bending investigation of intrinsic and fungible value. You bemoan

first the imposition of inflexible measures on vulnerable humans, and then you

recall that the value of money is inherently pliable. Kleeman has chosen an

insightful lens to examine the advantages and disadvantages of cost-benefit

analysis as well as the quantification of everything in a data-driven culture.

Interestingly, Nice's Qaly figure—which is a relative measure and an arbitrary

tool for comparison—was essentially generated out of thin air. Kleeman notes

that "when people treat tokens as if they truly represent the real price

of a human life, then danger arises."

Cuomo botched the

cost-benefit analysis he had suggested for lockdowns. He said, "To me, I

say, the cost of a human life... is priceless, period." In a similar vein,

former chancellor Rishi Sunak pledged to "do whatever it takes."

However, "whatever it takes" comes with a cost. After dividing the

lockdown's cost by the amount of life years saved, you get with £300,000, which

is ten times the Qaly threshold. Kleeman notes that more people could die now

or in the future if you callously disregard these figures as icy calculations.

A price on life may be an exploitation tactic, but it can also be a reasonable

measure of justice.