The Politics of Patronage in Scholarship-Related Literature

In literature, scholarships are often cast as beacons of hope—opportunities based on merit, aspiration, and perseverance. But behind this ideal lies a more complicated truth: that access to education and opportunity is frequently mediated by systems of power, influence, and favoritism. This undercurrent is what scholarship-related literature increasingly exposes and critiques through the theme of patronage.

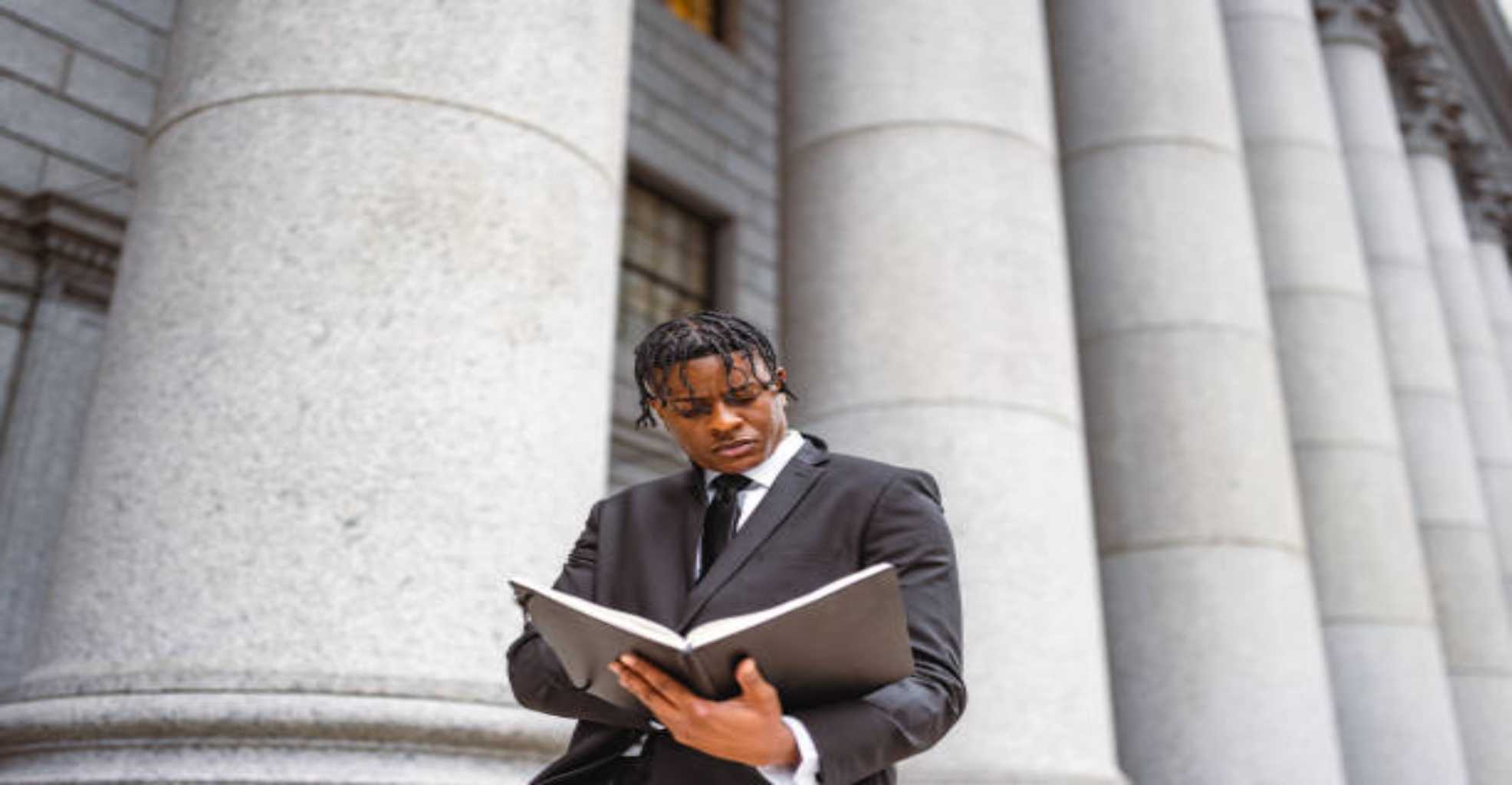

In many novels, especially those set within hierarchical societies or colonial/postcolonial contexts, the act of granting a scholarship is not merely an academic decision—it is a political act. A character’s access to education is often tied to who they know, where they come from, how they present themselves, or whom they serve. The donor-scholar dynamic, especially when dramatized in fiction, reveals a tension between meritocracy and manipulation, generosity and control, and liberation and indebtedness.

This blog post explores how fiction uses the politics of patronage to complicate our understanding of academic opportunity. Through examples from global literature, we will examine how characters navigate the benefits and burdens of being chosen—not just for their talents, but also for their usefulness to those in power.

1. Patronage vs. Merit: The Hidden Gatekeepers

In many novels, the question is not whether the protagonist is worthy of a scholarship, but rather whether they fit the social, political, or cultural mold of what donors expect. These stories often expose the arbitrariness of selection processes. A student's access to a scholarship may depend less on brilliance than on being in the right place at the right time—or having the right connections.

In Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o’s Weep Not, Child, the young protagonist Njoroge wins a scholarship, symbolizing hope for both his personal future and the dreams of his family. However, this hope is eventually crushed by political unrest, colonial violence, and the disintegration of the patronage systems that upheld the educational infrastructure. The colonial government’s support of African education is revealed to be conditional and deeply political. Njoroge's downfall is a sobering reminder that access to education is often contingent on broader power structures.

Similarly, in Chinua Achebe’s No Longer at Ease, Obi Okonkwo receives a scholarship from the Umuofia Progressive Union, a group of Nigerian elites invested in training "model citizens" for postcolonial leadership. But the scholarship is not a no-strings-attached gift—it carries immense expectations. Obi is burdened with the community’s hopes and pressured to conform to both colonial and traditional ideals. His failure to live up to these competing loyalties leads to his downfall. Achebe illustrates how scholarship patronage can trap rather than liberate.

2. The Scholar as Political Pawn

In fiction, those who receive scholarships often find themselves used as symbols or tools by larger institutions—governments, religious organizations, NGOs, or even private benefactors. These institutions use scholarships to shape a generation of thinkers aligned with their ideology.

In Edward Said’s autobiographical Out of Place, while not fiction, the dynamics of educational patronage are still highly relevant. Said explores how Western institutions offered him educational opportunities, but those offers came wrapped in expectations of assimilation and ideological alignment. Literature inspired by such narratives often examines how the scholar is reshaped to serve the values of the patron, raising questions about identity, autonomy, and co-optation.

In fictional stories like The Reluctant Fundamentalist by Mohsin Hamid, the politics of global education and Western patronage are central. The protagonist, Changez, receives a scholarship to Princeton and later a job on Wall Street. While his success is based on academic merit, it’s clear that he also represents a certain ideal: the talented outsider who adopts American values. As global politics shift post-9/11, Changez's place in that system becomes precarious, highlighting how patronage operates on implicit expectations of loyalty and gratitude.

3. Gendered Patronage and Power Dynamics

In literature, women who receive scholarships are often subjected to additional scrutiny and conditions. Their access to education can be tied to gendered expectations, moral standards, and male benefactors’ approval.

In Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions, the protagonist Tambu’s scholarship to a missionary school is a breakthrough. However, it is facilitated by her uncle Babamukuru, a patriarchal figure who dictates how she should think, behave, and succeed. While Tambu gains access to education, it comes with the price of obedience and suppression of her own voice. Her scholarship is both a gift and a leash—emancipation wrapped in control.

In Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus, the patriarch Eugene provides scholarships and educational support to his children and relatives. But this patronage is rooted in religious fanaticism and authoritarian control. For Kambili, education is not just a path to freedom, but also a space of resistance—one where she begins to question the authority that both nurtures and silences her.

These narratives show that educational patronage for women often comes with a moral price tag. Fiction reveals how gender and power intersect in the act of granting (and receiving) a scholarship.

4. Patronage in Colonial and Postcolonial Fiction

The theme of patronage is especially potent in postcolonial literature, where scholarships often symbolize the lingering hand of empire. The British, French, or American educational systems offer access—but at the cost of cultural erasure or political compliance.

In V.S. Naipaul’s A House for Mr Biswas, the scholarship path is always just out of reach. The idea of academic success remains deeply entangled with colonial values, and the characters’ pursuit of education reflects their internalized belief in British superiority. When characters do receive support from colonial structures, it's with the understanding that they will reproduce those same systems.

The critique here is sharp: scholarships in colonial contexts are not altruistic. They are instruments of soft power—designed to shape colonized minds into obedient administrators. Fiction that explores these dynamics complicates the idea of the scholarship as purely empowering.

5. Emotional Debt and Moral Expectations

Literary characters who benefit from scholarships often wrestle with a powerful sense of indebtedness—not just financial, but emotional and moral. This “emotional debt” becomes a form of patronage in itself, where the scholar feels obligated to fulfill the expectations of the donor, even at the cost of personal values or desires.

In The Secret History by Donna Tartt, while not a traditional scholarship story, the relationships between students and their professor Julian Morrow reflect a kind of intellectual patronage. Julian selectively invests in students, offering them elite education and cultural access. In return, they offer him loyalty, admiration, and their very identities. The imbalance of power mirrors that of scholarship narratives, where beneficiaries become dependent on and indebted to those who grant them access.

In more community-based fiction like The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri, the protagonist Gogol benefits from his immigrant parents’ sacrifices and educational investments. While not tied to a formal scholarship, the dynamic still reflects emotional patronage: Gogol's life is shaped by the unspoken expectation that he will live up to the opportunities bought for him. His journey reflects the psychological toll of being "sponsored" by others’ dreams.

6. Subverting the Patronage System

Some literature offers characters who actively subvert or reject the systems of patronage that come with scholarships. These characters question the legitimacy of their benefactors or walk away from educational institutions entirely.

In Tayari Jones’s Silver Sparrow, the protagonists navigate complex family and societal expectations. Although formal scholarships aren't the focus, the emotional and material patronage provided by an absent father shapes their educational trajectories and personal choices. Their rebellion is not just against parental authority but against the idea that opportunity must come at the cost of silence or compliance.

In more radical narratives like Kindred by Octavia Butler, though education is not central, the power dynamics of who controls whose mobility are starkly illuminated. Applying this lens to scholarship stories, we see a possibility: literature where characters reclaim autonomy, reject coercive patronage, and define education on their own terms.

Conclusion: A Necessary Critique

While scholarships in fiction often begin as hopeful emblems of transformation, the lens of patronage reveals a more troubling reality. Access to opportunity is rarely neutral. It is mediated by politics, privilege, ideology, and expectation. The donor is rarely invisible or disinterested, and the recipient is often shaped—not just helped—by the hand that feeds them.

Literature, in its power to dramatize the private and the political, invites us to ask: Who gets chosen? Who decides? And what does it cost?

By interrogating the politics of patronage in scholarship-related literature, we begin to see that education—while potentially liberating—is also a terrain of struggle. Fiction’s critical eye helps us understand that the path to learning is not always paved with fairness, and that even the most generous gift can cast a long, complicated shadow.