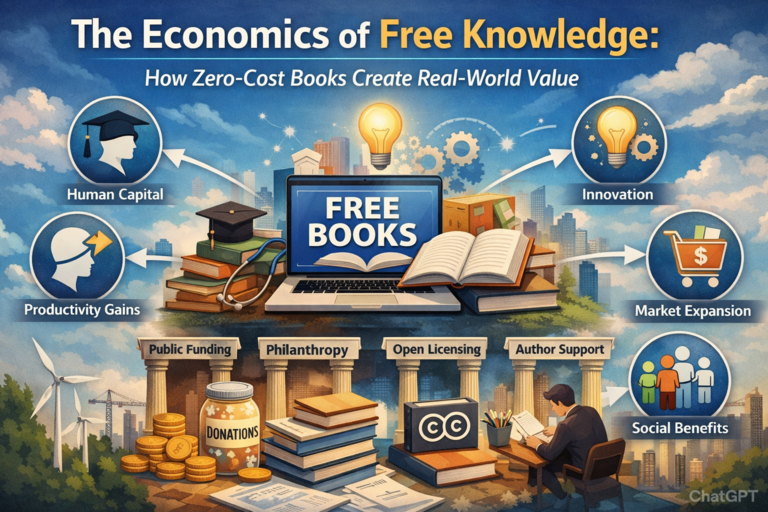

“Free books” can sound like a contradiction in economic terms: if something has a price of zero, how can it be valuablevor sustainably produced? The answer lies in a fundamental economic insight: price and value are not the same thing. In information markets especially, they often diverge dramatically.

A zero-cost book can generate enormous economic returns through higher productivity, reduced education costs, faster innovation, and broad social gains that rarely appear on a publisher’s balance sheet. When designed well, “free knowledge” is not anti-economic it is a different economic configuration.

This article explains how zero-cost books work economically, where their real value shows up, and what models can keep free knowledge sustainable over the long run.

1) Price Is Not Value: The Core Economic Distinction

Economists separate three concepts:

-

Price: What the reader pays at the point of access (sometimes $0).

-

Cost: What it takes to create, edit, design, host, and distribute the book.

-

Value: The benefit received by the reader and by society.

A book can be:

-

Free to the reader,

-

Expensive to produce,

-

And extraordinarily valuable.

When people talk about “free knowledge,” they are usually describing a different way of paying, not the absence of cost.

Two economic principles explain why this works:

Consumer Surplus

If a reader would have paid $20 for a book but receives it at $0, they gain $20 in consumer surplus. Multiply that across millions of readers, and the aggregate welfare gain becomes massive.

Free books dramatically expand consumer surplus because they eliminate price barriers especially for lower-income readers and students.

Positive Externalities

Knowledge generates spillovers:

-

A nurse using a free medical guide improves patient outcomes.

-

An entrepreneur reading a free business manual creates jobs.

-

A citizen accessing free legal information avoids costly errors.

These benefits extend beyond the individual reader. They create positive externalities value that accrues to society but doesn’t necessarily flow back to the author directly.

That gap between private return and social return is exactly why free models can make economic sense.

2) Why Zero-Cost Books Are Economically Plausible (Especially Digitally)

Near-Zero Marginal Cost

Digital books change pricing logic.

-

Fixed costs: writing, editing, formatting, design.

-

Marginal costs: delivering one more download almost zero.

When marginal cost approaches zero, pricing at zero becomes economically rational if funding comes from elsewhere (public funding, philanthropy, cross-subsidies) or if free access stimulates complementary revenue streams.

In traditional print economics, each copy costs money. In digital economics, once the first copy exists, distribution scales almost freely.

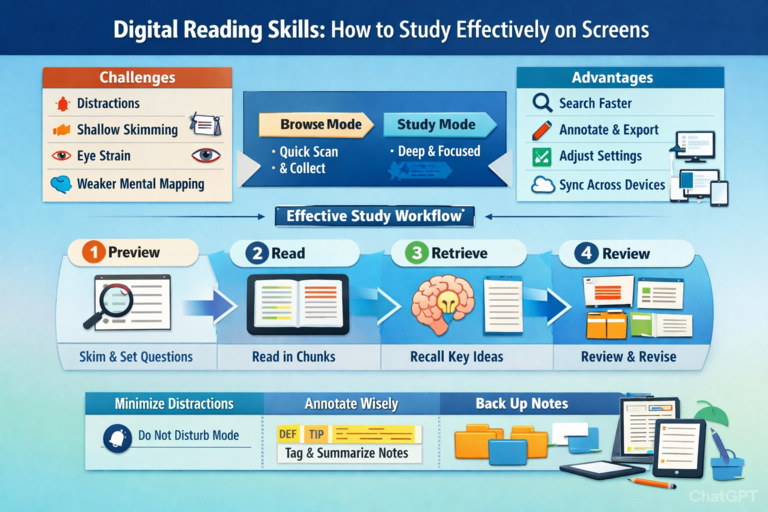

Information Goods Behave Differently

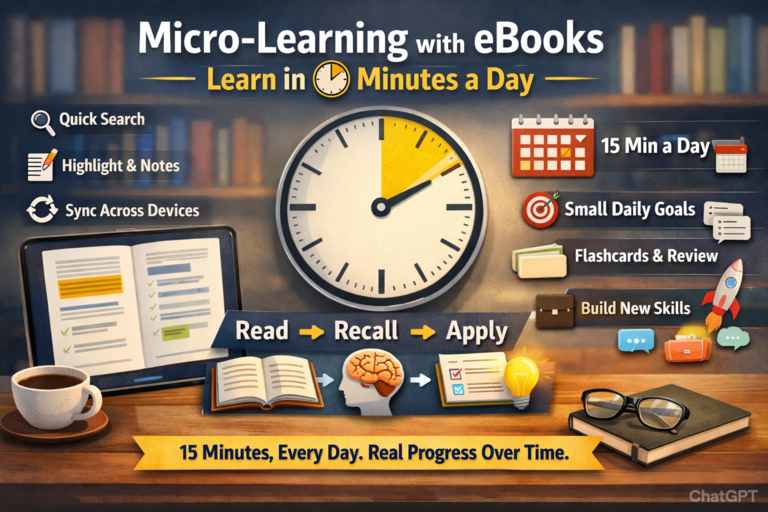

Books are “experience goods.” Readers don’t fully know their value until after consuming them. Free access reduces risk and encourages experimentation.

Wider adoption leads to:

-

Shared reference points

-

Network effects in learning communities

-

Reputation gains for authors

-

Faster diffusion of ideas

In knowledge markets, scale increases value.

3) How Free Books Create Real-World Economic Value

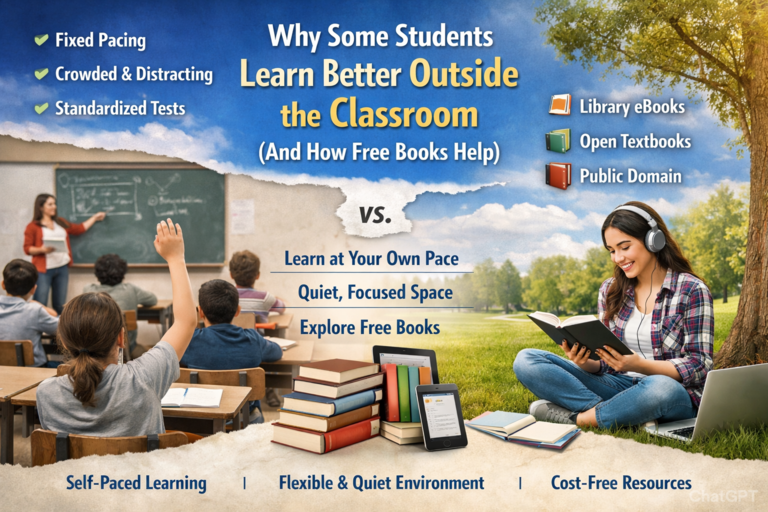

A) Human Capital Formation

The most powerful economic engine behind free books is human capital.

When access costs fall:

-

Students enroll more confidently.

-

Workers reskill more quickly.

-

Self-learners gain employable skills.

One prominent example is OpenStax, which provides peer-reviewed open textbooks used globally. By removing textbook costs, such initiatives redirect billions in household spending toward other needs while preserving instructional quality.

Even small improvements in educational access scale dramatically across entire populations.

B) Productivity Gains

Free access to technical manuals, programming guides, language resources, or health references reduces:

-

Errors

-

Downtime

-

Redundant problem-solving

-

Compliance failures

These gains are often invisible at the macro level but deeply meaningful in aggregate.

Better-informed workers make better decisions. Better decisions compound.

C) Innovation and Knowledge Spillovers

Innovation builds on prior knowledge. When foundational materials are free:

-

R&D cycles shorten.

-

More people participate in discovery.

-

Incremental improvements accelerate.

The cost of “standing on the shoulders of giants” falls.

Free access to foundational technical knowledge lowers entry barriers for innovators outside elite institutions expanding the innovation base of the economy.

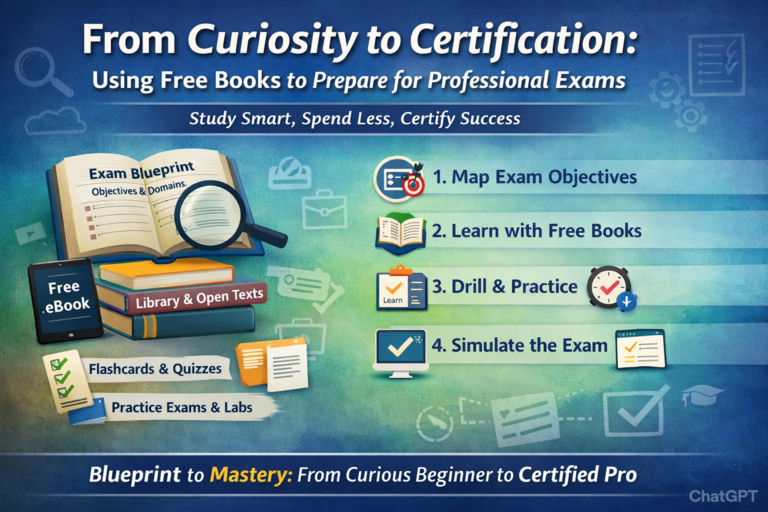

D) Complementary Market Expansion

Free books often stimulate paid demand elsewhere.

Complementary markets include:

-

Print editions (many still pay for physical copies)

-

Audiobooks

-

Courses and tutoring

-

Certification programs

-

Speaking engagements

-

Software tools

This resembles the “freemium” model: the book drives awareness and trust; complementary services generate revenue.

Free access can expand markets rather than cannibalize them.

E) Reduced Transaction Costs

Zero-cost books reduce search friction:

-

Readers can sample widely.

-

Educators can compare options.

-

Learners can switch resources easily.

This improves economic matching between skills and jobs, problems and solutions.

Lower transaction costs increase efficiency.

F) Social Returns With Economic Consequences

Free books also generate broader societal gains:

-

Health literacy reduces healthcare expenditures.

-

Civic literacy improves governance quality.

-

Educational access increases labor-force participation.

-

Literacy correlates with lower crime rates.

These may appear “social,” but they produce measurable economic effects over time.

Education’s social return often exceeds its private return making public or philanthropic funding economically defensible.

4) Where Free Books Come From

“Free” is not a single model. It reflects different funding and legal structures.

1) Public Domain

When copyright expires, works enter the public domain. Projects like Project Gutenberg distribute such works freely.

Public-domain books preserve cultural heritage and provide low-cost educational materials worldwide.

2) Public Libraries

Libraries operate on a “free at point of use” model funded by taxpayers.

They are a classic public-good institution: broad access generates widespread community benefit.

3) Open Licensing

Creative Commons and similar frameworks allow authors to permit free distribution under defined conditions.

Open textbooks and research publications shift funding upstream (grants, institutions) so downstream access is free.

4) Author-Led Free Distribution

Some authors offer early works free to build audience and monetize later via:

-

Sequels

-

Print collector editions

-

Membership communities

-

Consulting

-

Speaking engagements

Free distribution becomes a growth strategy.

5) Piracy (Legally Distinct)

Unauthorized copying creates free access but lacks built-in sustainability and fairness mechanisms.

Unlike open models, piracy does not compensate creators and can undermine long-term production incentives.

5) Who Pays When the Reader Doesn’t?

Sustainable free knowledge ecosystems typically rely on combinations of:

Public Funding

Governments fund creation and require open licensing, turning one-time expenditure into reusable public infrastructure.

Philanthropy

Foundations support literacy, translation, and open education when social returns are high but private returns are hard to capture.

Cross-Subsidy

Platforms bundle free books with paid subscriptions, premium features, or related services.

Patronage

Creators receive direct recurring support from communities.

Institutional Production

Universities already pay faculty to create knowledge. Publishing openly extends their mission.

The key insight: free access at consumption does not mean unpaid production. It means different funding structures.

6) Risks and Trade-Offs

Free knowledge is powerful but not frictionless.

Free-Rider Problem

If everyone benefits but no one contributes, production may decline.

Quality and Curation

When distribution costs drop to zero, content floods the market. Scarcity shifts to:

-

Editorial quality

-

Credibility

-

Discoverability

-

Trust

Curation becomes more valuable than distribution.

The Digital Divide

Free PDFs don’t help without:

-

Reliable internet

-

Devices

-

Accessibility features

-

Translation and localization

Zero price solves only one constraint.

Platform Gatekeeping

Even free content can be controlled by dominant distribution platforms that influence visibility and access.

Creator Livelihoods

Societies that want abundant free knowledge must maintain viable pathways for professional authorship.

7) Policy and Strategic Levers

To maximize real-world value from free books:

-

Fund open educational resources in high-enrollment and workforce-aligned fields.

-

Require open licensing for publicly funded materials.

-

Strengthen digital library lending systems.

-

Invest in metadata standards and discoverability tools.

-

Expand accessibility and translation initiatives.

-

Support sustainable creator funding models.

The goal is not just free downloads but durable economic impact.

8) The Bottom Line: Zero Price Can Maximize Social Welfare

Knowledge has unusual properties:

-

It is non-rivalrous (my reading does not reduce yours).

-

It generates spillovers (education and innovation benefit others).

-

It scales cheaply in digital form.

-

Its returns compound over time.

In such an environment, charging every reader the full production cost may suppress adoption and reduce total welfare.

The real question is not:

Should books be free?

It is:

Which funding and governance models best convert knowledge into widespread, long-term economic value while preserving incentives for high-quality creation?

When structured well, free books do not eliminate value they relocate it.

From checkout counters to classrooms.

From transactions to productivity.

From individual purchases to collective capability.

Zero price, in knowledge markets, can be an engine of abundance rather than scarcity.